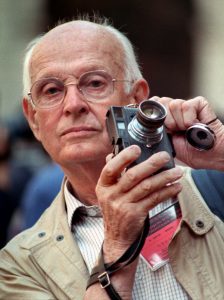

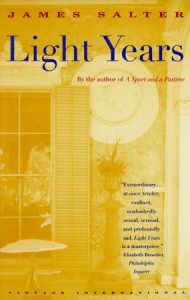

The New York Times obituary for the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson crossed my desktop last week, at just the right moment. I’ve been struggling—with a story, with my novel, with an essay—and I’ve also been reading James Salter’s beautiful novel, Light Years. I recognized right away a kinship between Salter’s writing and Cartier-Bresson’s ideas and images.

When Cartier-Bresson first picked up a tiny Leica 35mm film camera in 1931, he began a visual journey that would revolutionize 20th-century photography.

His camera could be wielded so discreetly that it enabled him to photograph while being virtually unseen by others — a near invisibility that turned photojournalism into a primary source of information and photography into a recognized art form.

Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the “decisive moment” — a split second that reveals the larger truth of a situation — shaped modern street photography and set the stage for hundreds of photojournalists to bring the world into living rooms through magazines such as Life and Look.

His signature shooting technique was to find a visually arresting setting for a photograph and then patiently wait for that decisive moment to unfurl.

I love this gift of “the decisive moment.” Sometimes Cartier-Bresson took only 3 or 4 images in an hour. His patience and vision were not in the service of an epiphany. His decisive moments were not bell clangs of sudden understanding, but instead moments of absolute clarity, distillations of time and place and people so true the image speaks of life beyond its frame. A notion similar to what the wonderful writer, Alison Lurie, has to say about fiction writing:

The only reason for writing fiction at all is to combine a number of different observations at the point where they overlap. If you already have one perfect example…you might as well write nonfiction. Indeed, you should…

But ordinarily you don’t have a single perfect example. Instead, over the years you’ve noticed, say, something about the way children behave at their own birthday parties, but none of your examples is complete in itself. So you invent a children’s party which never took place, but is ‘realer’ in the Platonic sense than any you ever attended. Fiction is condensed reality; and that’s why its flavor is more intense, like bouillon or frozen orange juice.

My story, about a woman in the pangs of middle age, a time when one begins to see the end in the distance, when family stretches away (sometimes with violence and sometimes with grace), when bodies start to fail, and marriages realign, was not hitting that Cartier-Bresson decisive moment. Sure, it’s full of scenes, the hospital, the dinner table, a long drive, but I haven’t yet found the moment. Consider this from Salter’s, Light Years.

Pure, empty days. The sea is sliver, rough as bark. Hadji has dug a hollow in which he lies, eyes narrowed, bits of sand stuck to his mouth. He always faces the sea. Franca has a black tank suit. Her limbs are shining and strong. She is afraid of the waves. Danny is more courageous. She goes out in the surf with her father; they scream and ride on their bellies. Franca joins them. The dog is barking on the shore.

Pure, empty days. The sea is sliver, rough as bark. Hadji has dug a hollow in which he lies, eyes narrowed, bits of sand stuck to his mouth. He always faces the sea. Franca has a black tank suit. Her limbs are shining and strong. She is afraid of the waves. Danny is more courageous. She goes out in the surf with her father; they scream and ride on their bellies. Franca joins them. The dog is barking on the shore.

That whistle of the sea in the long afternoon, the great beds of brown foam, of kelp brought up by the storms, the mussels, the whitened boards. To the west it is steaming, a long, brilliant stretch as if in rain. In the dunes Franca has found the dry husk of a beetle. She brings it, quivering in her hand, to Viri. It has a kind of single horn.

“Look, Papa.”

“It’s a rhinoceros beetle,” he tells her.

“Mama!” she cries. “Look! A rhinoceros beetle!”

She is nine. Danny is seven. These years are endless, but they cannot be remembered.

The scene makes my eyes sting. It’s so beautiful and vivid. Look at the precision of the sensory details, the sea is “rough as bark,” the dog has sand “stuck to his mouth,” they ride the waves “on their bellies.” And then there is the long vision of the distant storm that takes us away from the family out into the world only to return to the “husk of the beetle,” and the children, uniting the family wth their cries, “Mama!” “Look, Papa.” I feel so lucky to read these pages. I feel so lucky (and daunted) that I get to try to make the family in my story as true. As real.